Reports of ‘Id-ul-Fitr

at Woking, 28 May 1922

Khwaja Kamal-ud-Din leads prayer and gives khutba

From The Islamic Review, June–July 1922

|

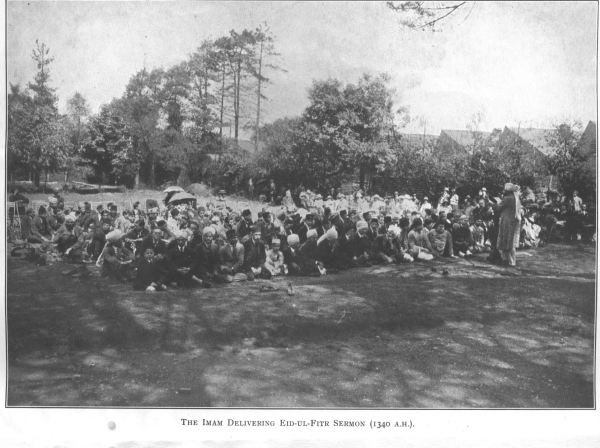

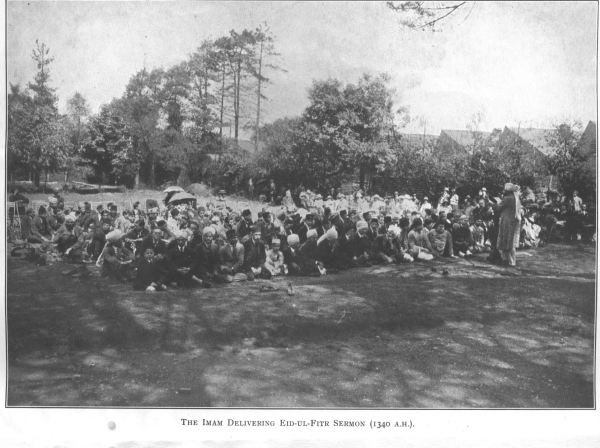

We present on this page reports and a photograph of ‘Id-ul-Fitr

at the Woking Mosque on Sunday 28th May 1922, taken from The

Islamic Review, June–July 1922. This is presented as an

example of the celebration of such festivals at the Woking Mosque

in the early years of the Woking Mission, to illustrate how these

occasions were conducted and the kind of international Muslim dignitaries

who graced them by their presence.

The photograph below shows the khutba being delivered in

the grounds of the Woking Mosque (see this photograph in a larger

size).

We first quote below most of the report of this‘Id-ul-Fitr

written by Rudolf Pickthall in The Islamic Review, June–July

1922, pages 246–250.

THE EID-UL-FITR, 1340 A.H.

EID DAY 1922 (the

28th of May) broke with a cloudless sky, and a promise, duly redeemed,

of unstinted sunshine and intense heat.

The oasis of the Woking Mosque in its sylvan setting of pine, rhododendron

and the fresh green of woodland bracken, seemed more than ever a

reproach to the desert of brick and mortar and corrugated iron with

which Industrialism has sought, of late, to hem it in; while the

attendance was even greater than in previous years, Muslim being

present representing well-nigh every nation; and a brilliant diversity

of Eastern costume and headdress splashing the scene here and there

with unexpected colour.

By 11 o’clock — the hour of Prayer — it was estimated

that upwards of two hundred persons had arrived; over three hundred

sat down to lunch, which was served at 1.15 on the lawn and under

the trees; while the advent of a new and large contingent for the

afternoon lecture and the subsequent tea brought the attendance

of the day to a total of well over four hundred.

To one who is present at the Eid festival for the first time, it

is by no means easy to analyse his impressions, or, when analysed,

to record them. He is apt to be trammelled not a little by an old

point of view, seeking to reconcile it, in all its differences,

with the new; never doubting the while but that the two may be,

fundamentally, one and the same.

Religion and ceremonial have been so long and so closely associated

together in the minds of men, that mankind is prone to judge a Faith

— one way or the other — by the pomp of its externals;

some arguing that these, be they never so elaborate, are seemly,

if inadequate, attempts to express our veneration for Eternal Truth;

others, that their very magnificence is but a mask for make-believe.

Neither view is of course just; for Eternal Truth can surely stand

in need of no adornment from us, and yet, to withhold too straitly

the marks of man’s homage may tend perhaps to neglect or irreverence.

In a world of men, there is much to be said for Pomp and Circumstance.

The solemnity of chant and procession, incense and altar lights

with which the Catholic Church surrounds the mystery of its worship,

is not to be condemned as symbolizing something which most of its

worshippers have perhaps forgotten long ago — if, indeed, they

ever actually realized it — any more than it is to be commended

for a vain endeavour to breathe life into a valley of dry bones,

or to perpetuate the dying cult of a dead myth.

All these things may be so, the faith forgotten, the cult dying

and the myth dead; yet nothing that tends to promote a spirit of

reverence, to induce thought in the thoughtless, or to remind man

of his Maker, can ever be altogether mischievous or useless.

Is ceremony essential to devotion? And if it be so, and yet, in

excess, a source of danger, what is the measure of ceremony which

will serve to turn man’s mind to God, without, at the same

time, luring it, as it were, to earth?

To such a question the Eid Day ceremony seems to suggest an answer.

The very absence of what may be called, perhaps, the mechanics of

devotion, which the Catholic is too apt to take for granted, counts

for much. The stage-managed procession, the carefully trained choir,

the organist alert not to miss his “cue” — neither

to be premature with a kyrie or behindhand with an Amen

— the elaborately musical colouring given to the Creed and

the Lord’s Prayer, the strict precision of gesture and genuflexion,

all, things which, however excellent and seemly in themselves, must

fully occupy the thoughts and minds of those concerned with their

proper presentation — that is one picture. The other —

a carpet spread on the grass beneath the Surrey pines, the voice

of the Imam reciting the Quranic verses, the silent praying multitude,

high and low, rich and poor, one with another, wherein is neither

priest nor layman, prostrate, their faces turned towards Mecca —

has about it an altogether strange dignity, a solemnity that tends

to quicken rather than give pause to thought.

After the Prayers, the Sermon.

The Imam, Khwaja Kamal-ud-Din, spoke of “that great Mysterious

Power” which the Atheist seeks to express in terms of chemistry,

and the Agnostic doubts, simply because he does not know. He spoke

of the Attributes of God — how they are revealed in Nature

and how they may be revealed in man; they are there for all men

to follow, be they rulers or ruled; and that if both rulers and

ruled would even now, at the eleventh hour, set those Attributes

before them, the tumult and unrest which to-day threaten to engulf

the world like a tidal wave, would be stayed as by the Hand of God.

The address is printed in full elsewhere, but it may not be out

of place to recall here a further aspect, new and impressing, of

its argument.

Science in discovering new secrets of Nature, so called, is but

revealing God, and the laws of Nature, so discovered, illustrate

one after another the Attributes of God precisely as those Attributes

were revealed to the Prophet Muhammad 1300 years ago and recorded

in the Holy Quran.

The theme is to modern ideas, however unconventional even, sufficiently

startling; but the preacher handled it fearlessly, indeed convincingly,

and his earnest eloquence and close reasoning, couched in language

which even the least academic could understand, produced a profound

impression.

… …

The Afternoon Lecture, which dealt with God’s message to mankind

— that it has been directly revealed to all nations and not

one alone — was largely attended, that is to say, as largely

as was humanly possible. But the beautiful Mosque — the princely

gift of Her late Highness the Begum of Bhopal — a gem of a

building, perfectly proportioned and a delight to the eye, is all

too small for a gathering such as this, and could barely contain

one tenth of those who were anxious to enter. Had the weather been

wet, the success of the day and its memories must, for this reason,

have been marred.

After the lecture, tea; and a general intermingling of groups and

conversation, and so a striking and memorable day drew to an end

— a day not, it may be, without its answer for many whose minds

are “clouded with a doubt”.

RUDOLF PICKTHALL

Reports in the British national and Woking local press

The same issue of The Islamic Review (June–July 1922,

pages 250–256) reproduces six news reports of the occasion

from the British press. We quote four of these below.

Daily News, 29th May 1922:

END OF A MONTH’S FASTING

AN ISLAM FESTIVAL AT WOKING

MOSQUE — BRITISH ADHERENTS OF EASTERN FAITHS

There has been rejoicing in Islam — fervent prostrations

in the name of Allah at the Mosque of Woking, the Moslem prayer-house

which you can see through the trees outside the railway station.

For the first time for thirty days all Moslems have eaten

to-day between sunrise and sunset. Now the Month of Fasting

is over and the great feast of Eid-ul-Fitr has been held in

the cool shadow of the scented pines. From now onward it is

permissible for Moslems to eat in daylight.

A British peer, an Indian millionaire importer from Mincing

Lane, and British followers and their blue-eyed Saxon wives

who have answered the clarion call of Islam, joined to-day

in the festival.

Lord Headley, who is the president of the British Moslem

Society, is said to be our second peer who has embraced Islam,

the first having been the late Lord Stanley of Alderley.

The Mosque at Woking is the only one in England where the

stranger — the unconverted — is besought to enter.

It was the gift of the mother of the present Queen of Bhopal,

the only Indian state where a woman rules. Here, you can bathe

your fevered brow in the waters of Islam. Here is a fount

that never seems to cease its outpourings, where you can trace

and read the written word of Islam or its followers lying

at the crystal depths of its gushing waters.

It seemed as if an Eastern sun shone down upon the Mosque

lawn this afternoon, where Arab, Egyptian, Indian and Englishman

and Englishwoman rejoiced exceedingly, and said: “Allahu

Akbar” — God is great. Some of the Englishwomen

were clad in silken Oriental robes, and broke bread at the

same table as Arab potentates in native dress. The Afghan

Minister and the Turkish Chargé d’Affaires, the

Palestine delegation and the representatives of Hedjaz and

Irak broke their fast.

PRAYERS ON THE CARPET

A vast Oriental carpet was spread on the lawn and strange

postures of prayer were watched by porters and navvies on

the railway line. Then, in the name of Allah, those who rejoiced

raised their hands to their ears, then folded their hands

across the body and placed them on the knees and bowed the

head and body. In the final prostration the body touched the

carpet.

Then came the feast, which was spread on white tablecloths

beneath the trees. It consisted of: Rice cooked in meat gravy

and butter; currie, potatoes, and meat; blancmange and drinking

water.

The Imam of the Mosque, a gorgeous figure who wore a raiment

of many colours, spoke on the subject of “Islam as the

basis for a world creed,” which was followed by an English

tea of bread-and-butter and pastries. |

Daily Telegraph, 29th May 1922:

ISLAMISM IN LONDON

Moslems throughout the world yesterday celebrated the great

festival of Eid-ul-Fitr, Kuchak Bairam — which marks

the conclusion of the Month of Fasting. It was celebrated

in London by a picturesque and notable gathering at the Mosque,

Woking, the only Mosque in England — which was the gift

some thirty-five years ago of the ruler of Bhopal. Indians,

Arabs, Turks, Syrians, Afghans, and Moroccans were among the

races of the world, and of the British Empire in particular,

who were represented at the service conducted by the Imam,

Khwaja Kamal-ud-Din. Many of the devotees brought their English

wives and children with them. They formed a strange congregation

under the trees of the lawn of the Moslem Mission House, the

little Mosque being too small to hold them all. At eleven

o’clock the muezzin was heard from the temple calling

to prayer. The congregation thereupon gathered in rows on

the greensward facing towards Mecca. In the front rows came

the men, and behind them their women. All of them discarded

their shoes, and performed the familiar salutations by raising

the hands to the head. The Imam then delivered a brief religious

address in which he emphasized that the Moslem religion is

essentially a universal religion whose broad ancient tenets

and benign toleration embrace members of all the great races

of the world. Fasting, too, was common to the Moslem, Christian,

and Jewish faiths. Purification came with fasting. The illumination

of life by which alone we could see God came with fasting.

At the conclusion of the Month of Fasting the Moslems in England

were glad to meet together again and to meet their English

co-religionists and friends.

At the conclusion of the simple service the congregation

greeted and embraced each other in Moslem fashion, and afterwards

took part in a very pleasant and appetising repast in the

open air under the trees, in the course of which the members

and staff of the mission, rich and poor alike, vied with each

other in discharging the kindly office of host and servant,

irrespective of social station. Tea followed in the afternoon

after a further religious celebration, and afterwards the

visitors returned to London.

Among the notable persons present were the Princes of Mangrol,

the Persian Chargé d’Affaires (in the unavoidable

absence of the Minister in Paris), the Afghan Minister, the

Turkish Chargé d’Affaires, the President and Secretary

of the Palestine Delegation, and representatives of Hedjaz

and Iraq. |

Note by Website Editor: ‘Minister’

was the term for Ambassador. ‘Hedjaz’ refers to what is

now Saudi Arabia.

Morning Post, May 29th 1922:

MOSLEM FESTIVAL AT WOKING MOSQUE

The Moslem festival of Eid-ul-Fitr Kuchak (Little) Bairam,

which marks the conclusion of the Month of Fasting, was observed

at the Mosque, Woking, yesterday.

Among those who attended were Lord Headley, the Princes Aziz

and Sadiq of Mangrol, the Afghan Minister, the Turkish Chargé

d’Affaires, the Chief Secretary of the Persian Embassy,

the President and Secretary of the Palestine Delegation, the

Nawab Sahib of Tohru, and representatives of Hedjaz and Irak.

Muslims from Arabia, Syria, India, America, Afghanistan, Turkey,

China and Java constituted the congregation.

Khwaja Kamal-ud-Din, the Imam of the Mosque, who conducted

the service, delivered an address, in which he said that things

created were sustained, and brought to their final perfection

under a perfect system of laws and regulations, which he would

sum up under three heads: the law of creation, the law of

sustenance, and the law of evolution, and Allah was the creator,

sustainer, and evolver of the various worlds around us. That

Mysterious Power was the same as the laws and forces of Nature,

which worked as did the Creator, and so it was that science

and religion were in perfect harmony. He exhorted his hearers

to study the Quran, on every page of which was inscribed the

name of Allah reproduced in ninety-nine forms, each one of

them representing His various attributes. If they lived up

to these attributes their morality would be secured; to deviate

from them was to tread the path of sin. As God was merciful,

so let them be merciful to others, even though they were not

of their nationality. God had not shown partiality in the

matter of any nationality, and if we did not show partiality

for race, creed, or colour, all unrest in the world would

be over. |

Woking News and Mail, June 2nd 1922:

MUSLIMS END MONTH OF FASTING

PICTURESQUE ISLAM FESTIVAL

AT THE MOSQUE

Sunday was the conclusion of the month of fasting in the

Islam religion, and all Muslims that day ate for the first

time for thirty days between sunrise and sunset. To celebrate

the Muslim festival of Eid-ul-Fitr Kuchak Bairam several hundred

Muslims of all races and colour made the pilgrimage from far

and near to attend the festival at the Woking Mosque in Oriental

Road.

Under a sky of azure blue, beneath the rays of a tropical

sun, and surrounded with scented pine trees, the faithful

gathered on the rolling lawn in front of the Mosque ready

for the call to prayer. The scene was gorgeously spectacular

to the visitors’ eye, and brilliant sunshine showed up

to wonderful effect the variety of colour to be seen in native

costume worn by both sexes. Every race seemed to be represented.

There were Arabians, Egyptians, Hindus, Afghans, Turks, Chinese,

Americans, Javanese, Syrians, etc., some in robes of many-hued

colours representative of their race or rank, some in correct

English dress, while others wore European dress with a distinctive

fez or turban. Some, on the other hand, were accompanied by

their English wives. There was a very large percentage of

English Muslims present, and the many English visitors who

had been given an invitation to attend at the festival were

given a cordial reception and made to feel at ease, for this

is an occasion when the Mosque is a common meeting-ground,

when colour, creed or caste is not considered, when Prince

and ruler meet peasant and subject on a common footing. Some

of the Englishwomen were clad in Oriental robes.

The company was much larger than in previous years, and showed

an increased number of English adherents to the Eastern faith.

Among the notabilities present were Lord Headley (the President

of the English Muslim Society), the Princes Aziz and Sadiq

of Mangrol, His Excellency Sardar Abdul Hadi Khan (the Afghan

Minister), the Turkish Chargé d’Affaires and staff,

the President and Secretary of the Palestine Delegation, representatives

of Hedjaz and Irak, the Nawab Sahib of Tohru, Secretary of

the Persian Embassy, and the other representatives of the

nationalities mentioned formed the congregation.

A GREAT MYSTERIOUS POWER

A large Oriental praying carpet was spread on the wide lawn,

and when the time arrived the call to prayer was sounded throughout

the grounds, the faithful assembling and prostrating themselves

on the carpet, having first removed their shoes. A large percentage

of the general public were accommodated with chairs at the

rear, where they watched the proceedings, so strange to European

eyes, with interest. In the name of Allah the prayers were

led by the Imam of the Mosque (Khwaja Kamal-ud-Din), who afterwards

read from the Quran and delivered an eloquent address in English

on Religion. He set out the tenets of the Islam faith, and

said that behind all laws of nature and others, behind everything

that had been discovered by man, behind all things, there

was a great mysterious Power. Putting the whole thing briefly,

this Power was the Creator, Maintainer and Sustainer of the

universe. The little that was known of the great Power at

work behind the scenes came from the knowledge of the laws

of nature. Every moment creation was going on, and if the

Unseen Power could be accepted as the origin of such it could

be rightly attributed the title he had named. The Imam went

on to speak of the Quran, and characterized its moral code,

and then spoke of the conflict which there should not be in

religion if they believed in the Unseen Great Mysterious Power

who made no difference in colour or race. False theology and

untrue science were at daggers drawn. If they were to have

comfort and civilization, and to secure perfect happiness

or success in life, then they must, in the words of Muhammad,

imbue themselves with Divine attributes. Islam meant complete

submission to Divine laws and a Muslim was one who submitted

to those laws. There was not one law discovered by man that

could not be traced to the Mysterious Power. He spoke of the

guidance the Quran gave to many millions of people, and also

referred to the ninety-nine names of God in the Quran. In

conclusion, he asked the faithful if they had ever contemplated

those ninety-nine names of God. If they had not, then their

prayers were a farce. God was merciful — let them be

merciful to others. God was just — let them be just.

All over the world to-day there was a great upheaval between

rulers and ruled. If those rulers would only walk humbly with

the Lord, who knew no difference between race and colour,

then their troubles would be over.

Following the address the faithful embraced each other, and

the company then sat down to a luncheon at which native dishes

figured, among which were rice cooked in meat gravy and butter,

curry, potatoes and meat, blanc-mange and drinking water.

The lunch was served on white tablecloths on the lawn. Afterwards

many of those present made a tour of inspection of the surrounding

countryside, and later returned to an English tea of bread

and butter and pastries. After tea the festival was brought

to a conclusion. |

Note: There are two more reports of this occasion from newspapers

quoted in The Islamic Review (from Daily Herald, May

29th and Woking Herald, June 2nd) which we omit to avoid

repetition.

|